A Note on the Translation from German

into English

The short biographies are based on the in-depth research and highly detailed texts written by the historian Hans-Jürgen Kremer, published in Exodus, Vertreibung, Shoah: Vom Leben und Sterben der Juden aus Germersheim 1933/1945, ed.

Verein Interkultur Germersheim e.V., Germersheim 2021.

The translations into English were done by the participants of the 2022 summer semester seminar „Translating historical and biographical texts from the Shoah: Stumbling Stones in Germersheim“ at the Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz, School of Translation, Linguistics and Cultural Studies, Department of English.

Teacher: Prof. Dr. Sabina Matter-Seibel; students: Denis Antony Francis, Anja Bär, Rahel Hoppe, Janina Kempkes, Patricia Keßler, Desiree Klein, Tobias Panczyk, Graziella Sari, Melissa Schmidt, Elizabeth Sexton, Theresa Stoelzel-Elsner, Marta Stoinska, Liliane Urich, Tamara Weidmann.

The School of Translation, Linguistics and Cultural Studies was asked to translate the biographical texts on the Jewish citizens of Germersheim into various languages in the spring of 2022, when the artist Gunter Demnig laid the stumbling stones in memory of those who were taken from their homes in Germersheim and murdered in concentration camps. As the University of Mainz – and especially the School of Translation, Linguistics and Cultural Studies on the Germersheim campus – values diversity and attracts students from more than 60 nations around the world, this project seemed perfect for us. Our group responsible for the translation into English, started working on the texts, reading historical and biographical books and articles on the Holocaust in both German and English and reviewing the academic literature on Shoah writing during the „project week“ in May. Soon we found the project more difficult and emotionally draining than we had expected. It forced all of us – with our various national and cultural backgrounds and personal involvements – to take a stand beyond explaining translation decisions. We would therefore like to give a brief insight into our various predicaments below.

The translated biographies will be available on the homepages of the Verein Interkultur and the City of Germersheim. We therefore assume that our readers will be both residents of Great Britain, the United States of America, and other English-speaking countries as well as speakers of various languages who use English as their lingua franca (esp. tourists once the QR codes at the stumbling stone sites are in place). Since most Jewish residents of Germersheim who managed to escape the Nazi regime chose the United States of America as their land of exile and since the people most likely to research their ancestors are Americans of Jewish descent, we decided to use the US American variant of English, including the way the dates are written. We also tried to keep the texts easily understandable for those readers whose mother tongue is not English. If we had to resort to specialized language, we provided additional explanations. In general, we coped with the problem of the „generation gap“, i.e., the vast difference in knowledge between those who lived through the Nazi regime and their children as compared to the younger generations that have no familial connections to the Nazi period, by adding pertinent historical and political information. We translated old and sometimes obsolete terms for professions, customs and other items as well as military terms from the First World War by words that are still in use today, but nevertheless connote the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

As it was to be expected, our main issue was the translation of Nazi terms. For some of them an English translation is well established, e.g., „National Socialist Party“. Others needed additional information, like „Kristallnacht“, a term used in the United States for the German „Novemberpogrom“, but unknown in most other Anglophone countries. It therefore needed an explanation, „Kristallnacht, ‘the night of broken glass’, in which synagogues were burned and Jewish businesses looted.“

Most heart-wrenching to deal with were the euphemistic Nazi terms whose purpose was to play down the horror. Not only does „Osttransport“ translated as „transport“ or even „deportation“ fail to convey the dread of that last journey to certain death, but it even perpetuates the inherent trivialization. We therefore translated it as „transport to an extermination camp in the Eastern part of the German Reich“ to give voice to the terrible truth. Another example is „Machtübernahme“ or „Machtergreifung“, the common German phrases for the moment the Nazis took over. If we say „to seize or to take power“ does that not connote a coup d’état, a violent incident, by which the population is overwhelmed when indeed the Nazis gained power via an election, by a popular vote? We did not want to relieve the German population of their complicity and translated „after the Nazis came to power“.

When tackling racist terms like „Blutschande“, „Mischlinge ersten Grades“, „jüdisch versippt“ we borrowed from British and American history, from the equally racist ideologies of colonization and slavery, and employed expressions like „miscegenation“, „mixed race“, „half-blood“. Another strategy was to counteract the geographical, military, and linguistic appropriation of Northern and Eastern European countries by the Nazis. The Germanized names routinely used for concentration camps outside of Germany were retained, but amended with the true place names and resituated in their regional and national settings, i.e., „camp Kulmhof, Chelmno, present-day Poland“.

Last, but not least, how to articulate the many deaths in the biographies? We decided to bear witness to the way the lives of Jewish citizens of Germersheim ended by choosing different terms: if they perished in a concentration camp, we called them „murdered“. We employed the austere term „died“ if their death was a consequence of persecution and denigration. The often-used euphemistic term „passed away“ was chosen only if the death occurred before or long after the Nazi regime.

We hope that the texts we translated will provide an instructive rendering of a very dark chapter in history and will prove a powerful reminder to never fall for any kind of propaganda again.

Germersheim, July 2022

Sabina Matter-Seibel and the participants of the project seminar

1a. Ernst Cahn and family (born in Germersheim, no stumbling stones)

1b. Otto Cahn and family (lived in Germersheim, Hauptstraße, no stumbling stones)

The families of the merchants Ernst Cahn (1873-1946) and Otto Cahn (1882-1920) were not related, but were both from Rülzheim, a center of rural Jewish life in the Palatinate region.

Ernst Cahn, whose father, Raphael Cahn, was a board member of the local Jewish religious community of Germersheim, left his birthplace and prospered in Mannheim in the wholesale business. Ernst had three children, Elise (deceased in 1919), Erich and Kurt.

Otto Cahn, son of the grain merchant Isaak Cahn, took up residence in Germersheim at the beginning of the 20th century. He took over a store specializing in women’s clothing and fabric from the widow of the Jewish merchant Gustav Cahn. In 1912, he was voted into the Synagogue Committee of Germersheim. In 1907, he and the merchant Noë Rosenbaum were also registered as owners of the cigar factory Lorenz, in the neighboring village of Lingenfeld.

Otto Cahn and his wife Hedwig’s three sons, Hans, Fritz und Walter Wolfgang, were all born between 1912 and 1915 in their residence located at Hauptstraße 136, Germersheim. Otto Cahn was drafted to serve in the First World War which had a negative impact on his already poor health. Two years after his dismissal from the military service, he passed away at the young age of 38. His widow managed the fabric store and took care of their three little boys. Adding to the already economically difficult situation, the National Socialist (Nazi) flood of new regulations led to a toxic atmosphere on a private, social and political level after 1933. Discrimination and systemic degradation laid down by the law were often willingly abided by, especially once the Nuremberg Laws came into effect, whose purpose was to „preserve the German blood“. The new regulations became part of the Cahns‘ everyday life. An example is the ban imposed in December 1935, which forbade the employment of a 24-year-old maid „of German blood“, Amalie Billmeyer from Lingenfeld, because the son Walter, at that time 20 years old, also lived in the Cahn household. The authorities were worried that a relationship between the two young people might lead to „racial defilement“. Consequently, Hedwig Cahn and her three sons emigrated to the USA between 1936 and 1938.

In the fall of 1938, Ernst Cahn’s sons Erich and Kurt also managed to emigrate to the USA. However, Ernst and his wife did not. Having been forced to give up their spacious and comfortable apartment in downtown Mannheim, they were finally deported to the internment camp in Gurs in the south of France on October 22, 1940. In the camp, the couple could not stay together, as the barracks were usually separated by sex. In December 1941, their immigration application was successful, and they were able to travel to their country of refuge, the USA, via the internment camp in Les Milles – in the nick of time before the German Reich declared war on the USA.

2. Auguste Dreyfuß (stumbling stone at Oberamtsstraße 14)

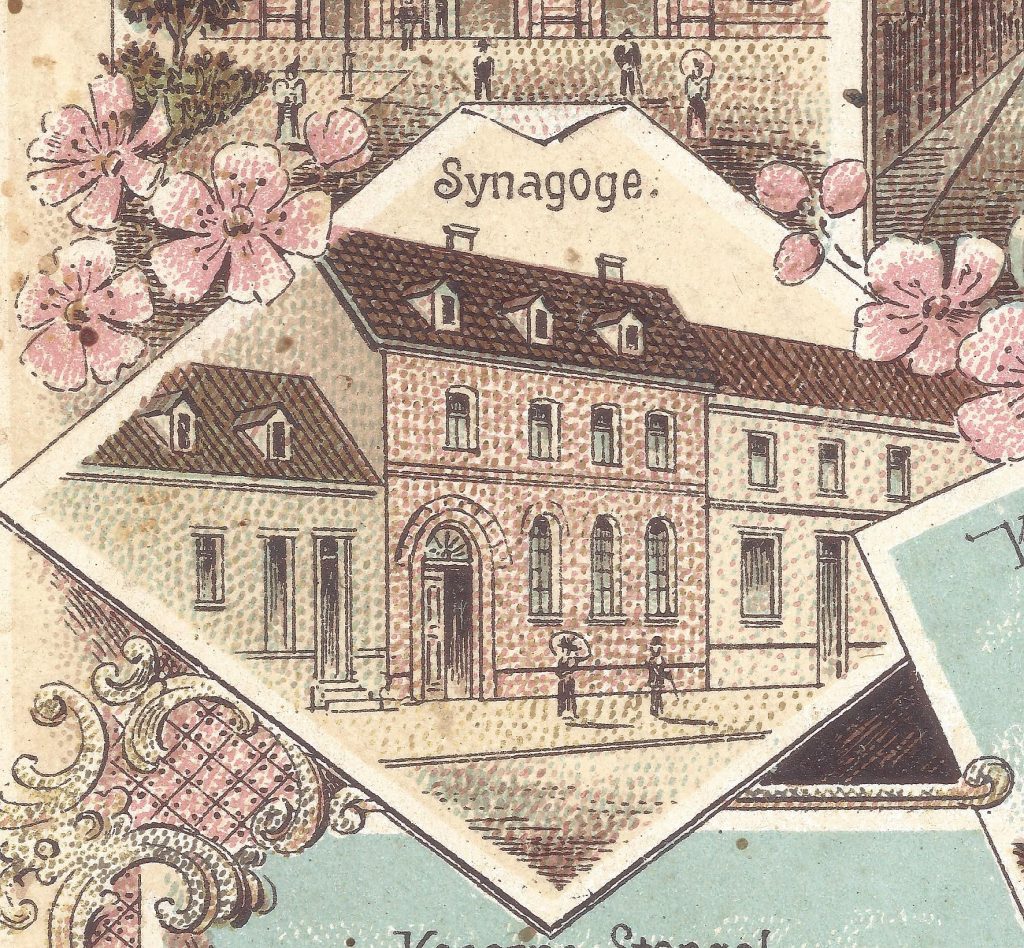

Four weeks before Adolf Hitler was appointed Chancellor of Germany in January 1933, the widowed Auguste Dreyfuß celebrated her 73rd birthday. Her home was in a building located at 203 Oberamtsstraße, next to the synagogue and the former officers‘ mess hall that was part of the defunct fortification. Back in 1897, her deceased father, Sigismund Dreyfuß, had owned a men’s clothing and wool garments shop in the same building. After the death of her mother in 1901, Auguste was the sole owner of the business, until she leased it to the Schmitt family in the 1920s, who turned it into a grocery store.

Auguste Dreyfuß, in spite of her wealth, had always lived a life of seclusion, which allowed her to avoid Nazi discrimination and humiliation for a while. However, in September 1935, the situation became unbearable. The newly enacted Nuremberg Laws under the Nazi regime alienated the civil liberties of German Jews and turned them into second class citizens. The Reich Citizenship Law declared them citizens without civil rights. From that point on, Jewish households were – among many other restrictions – not allowed to hire German citizens under the age of 45 for domestic aid. Dreyfuß was affected by this law since Juliana Burck from the nearby village of Kuhardt assisted her in daily matters.

Auguste Dreyfuß passed away in May 1939 and was thus spared deportation, which started one year later. Ten days before her passing, Dreyfuß drafted a handwritten will, in which she deeded 80% of two residences as well as two agricultural properties to the City of Germersheim and 20% to Juliana Burck, who had married. The matter was litigated and in 1942, the German courts conveyed the property to the City of Germersheim, whose mayor, Otto Angerer, was a member of the Nazi party. The City was also awarded the 7,666 Reichsmarks, a great sum at that time, which Dreyfuß had specifically intended to bequeath to the poor in town.

3. Eugen and Otto Ehrmann (born in Germersheim, no stumbling stones)

The brothers Eugen (1895-1943) and Otto Ehrmann (1898-1942) both spent the first years of their lives in Germersheim, the town they were born in. At the end of the 19th century, their father, Ferdinand Ehrmann, gave Jewish children religious instruction and was the prayer leader of the Jewish community. He married the local merchant’s daughter, Karoline Levy. The family moved to the town of Landstuhl, where Ferdinand passed away in 1911.

The tight financial situation for the widow Karoline Ehrmann and her sons improved once the older son, Eugen, finished his commercial apprenticeship as a bookkeeper and was able to contribute to the family income. However, in May 1917, Eugen was conscripted into military service and deployed to the Western Front. He suffered from many war injuries and was buried alive under debris in July of the same year. He was released two weeks after the cease-fire. Eugen, at the time 23 years old, was awarded for his military accomplishments with a black Wound Badge and an Iron Cross, 2nd Class. After the war, the bookkeeper left the Palatinate region, which was occupied by French troops, and moved close to Offenbach am Main. In 1923 he married Johanna Schönmann, the daughter of the textile merchant Emil Schönmann and his wife Auguste. Eugen and Johanna lived in the Schönmann family house, together with their sons Horst and Erwin (born in 1924 and 1926 respectively), and led a modest lower-middle class life.

After the National Socialists (Nazis) came to power in 1933, the life of the family changed drastically: The grandfather and the grandchildren were kicked out of the gymnastics club, and to avoid discrimination, both Horst and Erwin Ehrmann left the local elementary school and attended a Jewish school in Offenbach in 1935. Due to severe restrictions, Emil Schönmann was forced to give up his business. During Kristallnacht in November 1938, when many Jewish-owned businesses, synagogues and homes were vandalised, Emil Schönmann and his son-in-law Eugen Ehrmann were arrested by the Gestapo (secret police force) and were brought to the Buchenwald Concentration Camp. In December 1938, they were released under the condition that they were to „immediately“ emigrate and to remain silent about their imprisonment.

That same December, the families moved to Frankfurt am Main. The labor market, which was reoriented to meet the demands of the war economy, turned Jewish employees essentially into forced laborers. Eugen Ehrmann began working at a Frankfurt horticultural farm and his wife Johanna worked in an industrial laundry facility in Niederrad. Their son Erwin successfully completed an apprenticeship at a Jewish training workshop in Frankfurt, and his brother Horst was a laborer at the company Alfred Teves GmbH (an important producer of car components and of weaponry during the war), working for a paltry 36 Pfennigs an hour.

On June 11, 1942, the two young men were deported from Frankfurt to Eastern Poland. In the Lublin area, newly arriving young, able-bodied Jews were rounded up to build the Majdanek Extermination Camp. The extremely harsh living and working conditions led to many deaths. At the young age of 15, Erwin died on August 3, 1942. His brother Horst died at age 17 on September 10, 1942. Their fate remained unknown to their parents. On September 15, 1942, the Ehrmann and Schönmann families were deported to the Theresienstadt Ghetto (in present-day Czech Republic) via Sonderzug (deportation train), in a group of 1,370 Jewish people from the Hessian region. On January 29, 1943, Johanna and Eugen Ehrmann were deported from Theresienstadt Ghetto to the Auschwitz Extermination Camp (in present- day Poland) and murdered. In May 1944, Auguste and Emil Schönmann were also murdered.

Eugen’s brother Otto moved from Landstuhl to Offenbach am Main in 1931. It is only known that he married Sophie Nussbaum in August 1936 and that they did not have any children. In September 1942, the married couple was deported from Darmstadt to the Treblinka Extermination Camp (also in present- day Poland). Shortly after their arrival, they were murdered.

In August 1939, Eugen and Otto Ehrmann’s mother, Karoline, lost her German citizenship. The timing of her official loss of citizenship indicates that the 63-year-old probably resettled in a foreign country. She is the only member of the Ehrmann family who possibly escaped the Nazi terror.

4a. Johanna Glaser (born in Germersheim, no stumbling stone)

Johanna Posner was born in Germersheim on December 5, 1877. She was the third of four children of the book printer Salomon Posner (1845-1891). In 1902, she married the Berlin merchant Leopold Glaser. They lived in Charlottenburg and Wilmersdorf, Berlin, until he passed away in the fall of 1929. Their only child, Ernst Fritz Glaser (1908-1999), was born in Berlin. Under the pressure of the Nazi regime, he emigrated to the USA. However, his mother Johanna did not manage to escape. On March 28, 1942, she was deported from Berlin to the Piaski Ghetto in Eastern Poland, which was built in the beginning of 1940, right after Poland was occupied by the Wehrmacht (German Imperial forces). Together with 985 other individuals, Johanna Glaser was part of the eleventh „Resettlement to the East“, which arrived at the train station Trawniki near Lublin after a two-day journey. From there, the victims were forced to march for twelve kilometres along a road leading to the ghetto. It is not known if Johanna, who on the transport list was labelled as „able to work“, was transferred from the Piaski Ghetto to the Trawniki Forced Labor Camp (in present-day Poland) together with 4000 other Jews in the fall of 1942. All facts suggest that the Germersheim-born Johanna Glaser died in the early summer of 1942, a few months before her 65th birthday.

4b. Dr. med. Ferdinand Kahn (grew up in Germersheim, no stumbling stone)

Ferdinand Kahn, who was born in 1866 as the son of the Germersheim merchant Karl Moses Kahn (1834- 1905), only spent his early childhood and his first years of school in Germersheim. He likely attended secondary school in either Landau or Speyer. Afterwards, he went on to study medicine in Würzburg, Munich and Berlin. In 1891, the 25-year-old Kahn received his M.D. and obtained his license to practice medicine. While he was an assistant to the well-known German dermatologist Max Joseph, Kahn was able to gain work experience for his own professional practice. Afterwards, he went on to specialize in dermatological and sexually transmitted diseases in Frankfurt am Main, where his parents, who were originally from Germersheim, were also living. He was one of the first dermatologists, as this medical specialization was just developing. In 1900, he married the local merchant’s daughter, Paula Meyerfeld. The couple remained childless.

In 1918, just shortly before the end of the First World War, Kahn proudly received the title of a Sanitätsrat (medical councilor) for his service as a specialized therapist for wounded soldiers. The doctor felt secure in his position and was caught off guard by the new political conditions that prevailed in Germany in the spring of 1933. The Nazis‘ calls for a boycott of Jewish professionals did not initially have their full effect in the case of highly specialized physicians like Kahn. In April 1933, the Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service removed the so-called „non-Aryan doctors“ from the public health system. Two weeks later, Kahn was no longer allowed to treat patients that were covered under national health insurance. More and more long-standing private patients also left his practice for fear of having to explain themselves for having consulted one of the ostracized „racial enemies“. Ferdinand Kahn had been listed in the Reichs-Medizinal-Kalender (Reich Medical Register), the annual publication of the German medical association, since 1895. However, in 1937 he was identified as „Jew“ in the register. Just like all the other Jewish physicians, Kahn finally lost his licence to practice medicine in 1938. Of the 8000 Jewish physicians only 285 had not left Germany by the end of 1938, among them Ferdinand Kahn, who seems to have been resigned to his fate.

In the summer of 1942, the municipal government of Frankfurt am Main dealt the final tragic blow to the Kahn family and ordered police to confiscate the remaining assets and the house of the Kahn family in preparation of the impending „evacuation.“ Paula (67) and Ferdinand Kahn (76) were deported from their residence to the Theresienstadt Ghetto (in present-day Czech Republic) via train on September 1, 1942. Ferdinand Kahn died in the ghetto on September 20, 1942. His wife Paula Kahn died shortly thereafter.

5. Auguste Kahn and Rudolf Kahn (no stumbling stones),

Max and Sofie Ebert and Ferdinand and Isabella Kahn

(stumbling stones at Hauptstraße 10)

Among the Jewish families in Germersheim, the Kahn family had the longest and closest ties to the town. In 1829, Ferdinand Kahn founded a clothing company in Germersheim, which since 1834 had been thriving, thanks to the demand triggered by the construction of the military fort. Ferdinand’s son Wilhelm and his grandsons August and Ernst Kahn, who ran the business together until 1914, expanded and adapted their range of goods to meet the needs of the military. As a result, they were considered the most renowned tailors in the Germersheim garrison in the second half of the 19th century. Their estate, located on the small creek Queich (at Hauptstraße 140), consisted of a spacious two-story residential and commercial building along with storage rooms in adjacent buildings. They even had one of the rare telephone lines. Although their business success was based on tailoring uniforms, the Kahns also supplied the population with fabric for men’s suits and women’s dresses as well as curtains, carpets, upholstery fabrics and bedding.

The Kahns‘ bourgeois-monarchist sentiments indicate how strongly the business orientation toward the army had influenced the family’s political self-positioning. The advertisements of the Kahn company from the early 20th century show that state and nation, crown and army had become new priorities in the mindset of assimilated Jewish families. Titles such as „Königlich bayerischer Hoflieferant“ (Royal Bavarian Purveyor) appeared under the coat of arms of the reigning Wittelsbach dynasty. In the years leading up to the 20th century, Ernst and August Kahn ran the company, while their father Wilhelm was active in local politics. In 1905, he was the first Jew to be elected to the Germersheim City Council.

August, who was married to a Nuremberg merchant’s daughter, Auguste Lederer, passed away at the age of 47, six weeks before the outbreak of the First World War. His son Rudolf Kahn (born in 1896), who had begun studying economics and law in Würzburg, converted from Judaism to the Protestant faith in 1915. He undertook this cultural-religious assimilation into the majority society during the heated wartime atmosphere. In the last weeks of the First World War, as a lieutenant in the reserves, he was honored with the Iron Cross, 1st and 2nd class. After the war, once he had received his doctorate, Rudolf Kahn moved to Berlin, where he married in the late 1920s. In 1934, he emigrated to Great Britain, because neither his conversion nor his German patriotic attitude could save him from militant anti- Semitism. In Great Britain, he was initially interned as a so-called enemy foreigner.

His widowed mother, Auguste Kahn, had left Germersheim in 1922 and had moved to Berlin- Charlottenburg in 1934, after spending some years in Munich and Meiningen/Thuringia. On July 20, 1942, the 69-year-old senior citizen was deported to the Theresienstadt Ghetto (in present-day Czech Republic) on the 26th so-called Alterstransport (deportation of Jewish senior citizens). According to the death notice of the Jewish Council of Elders there, she died of „intestinal catarrh“ on November 21, 1942, having already been in poor health.

Due to the sudden passing of his brother August in the summer of 1914, Ernst Kahn had become the sole proprietor of the family business. Following in his father’s footsteps, Ernst had been involved in local politics, serving on the synagogue committee from 1907 and on the city council from 1910, where he joined the liberal, right-wing Free Citizens’ Association in 1920. He laboriously managed the company through difficult war years and an economically turbulent post-war period until his death at the end of 1926. His only child, Ferdinand Kahn, born in 1895, was – like his younger cousin Rudolf – of a military and patriotic mind due to his upbringing and the political atmosphere at the time. The newly enrolled 19-year-old student of economics enlisted in the army immediately after the start of First World War in 1914. In the 1st Bavarian Foot Artillery Regiment, he spent the entire war on the Western Front and was decorated several times. The fact that the now 23-year-old soldier was promoted to lieutenant of the reserves in September 1918, without receiving the corresponding officer’s commission, is likely associated with the anti-Semitism that was spreading in military circles.

After Ferdinand Kahn was discharged from military service in 1918, he decided not to continue his studies and instead became a merchant in the commercial metropolis of Frankfurt am Main. There, in March 1921, he married Isabella (Bella), the daughter of his fellow merchant Max Ebert and his wife Sofie from Lower Franconia. The young couple stayed in Frankfurt, because Ferdinand doubted the profitability of his parents‘ business, which was threatened with bankruptcy and had been deprived of its most important source of income with the withdrawal of the Bavarian military at the end of 1918. When his father passed away in 1926 and his mother in 1927, Ferdinand Kahn – honoring family tradition – followed in his forefathers‘ footsteps. Since his parents-in-law also moved to Germersheim and formed a joint household, the family was able to maintain a modest level of prosperity.

A local branch of the Nazi party became active in Germersheim in the fall of 1926 and made anti- Semitism, which had already been a socially accepted disposition, omnipresent in everyday life. This began to weigh on the Kahn family. Three weeks after the Nazi regime came to power in 1933, all Jewish businesses were boycotted. On November 10, 1938, during the Kristallnacht, a night of rioting against Jews and their businesses, the 43-year-old Kahn was dragged out of his home und taken into custody. After being held in prison in Germersheim for 24 hours, Kahn was deported to Dachau Concentration Camp. On December 16, 1938, he was released from the camp and was urged to leave the country, which he did not do, but instead returned home. After almost two years, on October 22, 1940, Isabella and Ferdinand Kahn fell victim to the Judenaktion (Jewish Operation). Bürckel and Wagner, so-called Gauleiter, administrative heads of the regions Saarpfalz and Baden, planned to cleanse their respective areas of Jews. Just like the Mohr siblings and Gustel Töpfer, Ferdinand and Isabella Kahn were brought to the town Landau, where they were put on trains with other Jews from the Palatinate region. The families were deported to the Gurs Internment Camp in the south of France. They were only allowed to take a light suitcase and 100 Reichsmarks with them. In Gurs, the couple had to live in separate camps and in great deprivation. Kahn’s in-laws were brought to a Jewish nursing home in Mannheim, where Max Ebert soon died.

In March 1941, Ferdinand and Isabella were transferred to an internment camp in Les Milles, near Marseille, which was built for potential emigrants. Sofie Ebert, the mother-in-law, then 68 years old, urged close relatives who had already fled to the USA, like the merchant Joseph Freundlich, to sponsor the couple. On August 18, 1941, thanks to Freundlich’s intervention, the Kahns were released from the camp. They left Marseille for Lisbon via Spain, and from there crossed the Atlantic Ocean before finally arriving in New York on September 24, 1941. Six months later, the family applied for US citizenship. The 43-year-old Isabella Kahn earned a livelihood doing strenuous work in a factory in New York City.

Sofie Ebert, however, was not able to save her own life. On August 28, 1942, ten days after her 70th birthday, she was transferred to the Theresienstadt Ghetto. A month later, on September 29, she was deported to the newly built Treblinka Extermination Camp, near Warsaw. Immediately upon arrival and after undergoing a selection process on the loading platform, Sofie was brought to a gas chamber where she was murdered.

Back in Germersheim, the town was engaged in a quarrel over the remaining business premises and the plots of land which belonged to the Kahn family. The municipal savings bank in Germersheim decided in December 1940 to auction off the seized properties. In 1941, the savings bank sold the Kahn’s residence to the 27-year-old master shoemaker and Jungbannführer (leader of the Hitler Youth) Friedrich Köhler for 24,000 Reichsmarks – half of the sum was paid with a loan by the same bank. The four plots suitable for agriculture were managed by the Ortsbauernführer (local Nazi farmers‘ leader), Otto Frey. Meanwhile, the Nazi regime revoked the citizenship of deported Jews, with the 11th Ordinance of the Reich Citizenship Law coming into effect on November 24, 1941. This also meant that all properties of stateless Jewish owners were officially confiscated. Management and utilization of the Kahn’s assets were handed over to the Germersheim revenue office. The revenue office was now entrusted with the leasing of their pastures, fields, and gardens.

In 1949, the Isabella and Ferdinand Kahn applied for the return of property and for reparations. As in the case of many other Jewish families, the trial ended with a settlement, in which the loss was not nearly compensated. The local law office Kerscher made sure that the current owner of the Kahn house had to pay only 7,000 Reichsmarks in compensation. The low sum was based on devalued assets because of war damage and pre-1933 substantial debts, presumably „unrelated to the political circumstances“. Ferdinand Kahn, who still subscribed to the Heimatbrief (annual letter about local events) from his hometown of Germersheim, died in his residence in Queens, New York City on November 14, 1969.

6. Dr. med. Bernhard (Benno) Koppenhagen

(raised in Germersheim, no stumbling stone)

Bernhard (Benno) Koppenhagen was born in Germersheim in 1867 as the fourth child of Simon Koppenhagen and Rosine Weis from Mainz. The surname Koppenhagen refers to the paternal family’s Danish roots. Numerous family members were watchmakers and goldsmiths, which facilitated professional mobility, so many of them moved south in the mid-19th century. Koppenhagen’s parents had settled in Germersheim in 1860. Benno grew up in Germersheim and attended secondary school in Speyer until his father’s sudden passing in 1884. The family then moved to nearby Landau where he graduated from secondary school with excellent grades in 1886. Financed by his older brother, he studied medicine in Würzburg and found his first job as a doctor in the Thuringian town of Schleusingen in 1891.

In July 1895, Benno Koppenhagen married Olga, the daughter of Schleusingen’s mayor Ludwig Baecker. Olga was six years younger than her husband and they had two children, Herbert and Hertha. His siblings vehemently opposed their brother’s marriage and his later conversion to Protestantism. Koppenhagen’s relationship with his brothers, who lived abroad, ended and his Jewish roots were severed. The general practitioner performed surgery and assisted in childbirth in the municipal hospital, as well as working at schools and with the town’s poor. In his spare time, he wrote humorous stories about life in a small town.

The First World War marked a turning point in Koppenhagen’s life. Five days after the outbreak of the war, at the age of 47, he was conscripted as ward doctor in the military hospital, located in the fort of his hometown of Germersheim. Later, he was commissioned to lead different military hospitals in northern France. However, the doctor’s own health soon suffered, and he was worried about his injured son Herbert. In June 1916, Benno Koppenhagen was relieved from his duties at the French military hospital and returned to Germersheim and Würzburg to recover. In Würzburg, he worked as a military doctor until the war ended.

After the First World War, Koppenhagen came back to Schleusingen, where he worked as a vaccinator and founded a local group of volunteer paramedics affiliated with the German Red Cross. He enjoyed a good reputation as a general practitioner and gynecologist due to his professional competence, but soon had to fight against anti-Semitic propaganda. In the spring of 1933, the National Socialists (Nazis) came to power and called for the boycott of Jewish-run businesses all over the Reich. When the Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service came into effect, Benno Koppenhagen was dismissed from his position at the hospital. His right to work with patients insured in the public health system was also withdrawn, which meant that he had to depend on privately insured patients for income from this point forward.

In January 1934, as Koppenhagen’s career was coming to an end and his social isolation grew, he suffered a stroke resulting in one-sided paralysis and a speech disorder. Benno Koppenhagen gave up hope. On January 20, 1934, he had his nurse administer an overdose of morphine and died the same day. An SS doctor took advantage of Koppenhagen’s death and moved into the fully equipped doctor’s office. In the following year, his widow sold their house and moved to Wiesbaden. Koppenhagen’s daughter Hertha and his grandchildren survived the NS regime, the latter by means of forged certificates of Aryan heritage.

In Schleusingen, a street is named after Benno Koppenhagen M.D., whereas in his hometown of Germersheim there is nothing to remember him by.

7. Elsa Leiser (born in Germersheim, no stumbling stone)

Elsa was born in 1881 in Germersheim to Sara and Gustav Cahn (1839-1897) at Hauptstraße 136, where her parents both lived and ran their business. She had a sister Magdalene, three years her junior. The shop dealt in manufactured goods, women’s fashion, and textiles and offered the Jewish family a reliable income. After the passing of her father, Elsa left Germersheim at the end of 1903 and married the lawyer Julius Leiser (1876-1942) from Metz in Lorraine. Her mother continued to run the shop by herself.

Julius Leiser, who was admitted to the bar by the district court in Metz in 1902, opened a law office, which he ran until 1918 along with the politically influential Albert Grégoire. A high degree of professional competence, hard work and diligence gained the office a superb reputation. During the First World War, Leiser dealt with the legal affairs of the Gouvernement-Intendantur, a military branch in Metz, and in June 1917 he was awarded the Merit Cross for War Aid. As the region of Alsace-Lorraine was handed back to France, the 42-year-old Julius Leiser, now considered a persona non grata, had to leave his home in January 1919. According to the agreements made in the Treaty of Versailles, he was not considered to be French and therefore lost both his right to practice law and his right to residency.

The Leisers moved to Wiesbaden to start afresh. Their financial situation visibly improved as the accomplished lawyer quickly became a consultant for wealthy and prominent clients such as the sparkling wine manufacturer Henkell and the former German Crown Prince Wilhelm of Prussia. Leiser purchased a house and business premises. The status enjoyed by the married couple, thanks to the respect of the high society of Wiesbaden, crumbled as soon as the National Socialists (Nazis) came to power. On June 12, 1933, Leiser was fired from his position as civil law notary, by order of the Prussian Minister of Justice. Though he was still able to work as a lawyer, the number of his „Aryan“ clients – most notably the sparkling wine manufacturer Henkell, the family into which Joachim von Ribbentrop, later Hitler’s foreign minister, had married – sank considerably, forcing Leiser to downsize his offices substantially. A provision to the Reich Citizenship Law made in 1938 finally stripped him of his right to practice law.

Left destitute by the Jewish Capital Levy, imposed on richer Jewish families, the Leisers emigrated to the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg in January 1939, where they led a modest life. A precondition of their emigration was a payment of 24,442 Reichsmarks as a so-called Reich Flight Tax, a law which the Nazis used as a means to requisition part of the property of Jewish people forced out of the country. The return to normal life for the Leisers lasted only a short 16 months. In May 1940, the Wehrmacht (German Imperial Forces) occupied the small neighboring state, which was placed under a civil administration and treated as part of the Greater German Reich.

In the fall of 1941, the Leiser’s house in Wiesbaden was forcibly sold. The profits went to the civil administration in Luxembourg. It was probably for this reason that Leiser returned to Wiesbaden, where he was immediately imprisoned. Katharina Henkell – the widow of the former head of the sparkling wine manufacturer and von Ribbentrop’s mother-in-law – interceded on Leiser’s behalf and he was able to return home. There he passed away on September 24, 1942. His wife, on the other hand, suffered the horrors of further persecution. On April 6, 1943, the Germersheim-born Elsa was deported by train first to the Theresienstadt Ghetto (in the present-day Czech Republic), then to the extermination camp in Auschwitz (in present-day Poland). She was murdered with poison gas soon after her arrival on August 15, 1944.

8. Dr. jur. Wilhelm Masser (1915-16 Municipal Judge in Germersheim,

no stumbling stone)

In 1915, at the age of 33, the attorney Wilhelm Masser came to Germersheim when the Bavarian Ministry of Justice transferred him to the municipal court. His father David Masser, a cattle trader from Kitzingen, had married Josefine in 1880. She was the daughter of David Rosenheim, an affluent cattle trader. Being in business with his father-in-law, David Masser had been able to provide his sons Wilhelm (born in 1881) and Ludwig (born in 1883) with a good education.

Wilhelm attended a secondary school focusing on humanities and later studied law at the University of Würzburg. He continued his studies in Berlin and successfully completed his doctorate in administrative science. Shortly before he started his judicial career, Wilhelm married the music teacher Nelly Süßer in 1909, the daughter of a wholesale textile merchant from Würzburg. Wilhelm was appointed to the position of the second public prosecutor in Hof in northern Bavaria. In 1915, he moved to Germersheim, where he was appointed to the position of municipal judge. He and his wife lived on Bismarckstraße near the courthouse.

In October 1916, Wilhelm Masser was drafted to fight in the First World War on the Western Front in north-eastern France. Masser, who was of patriotic German mind, proved himself and was promoted to acting corporal in October 1917 and sergeant in July 1918. He was also awarded several Merit Crosses. After the war, he was appointed as a district judge in Munich, where the couple moved in September 1919. His daughter Elisabeth Johanna was born in Munich in 1920. In 1927, Wilhelm Masser was appointed as senior district judge.

After the National Socialists (Nazis) came to power, the life of the Masser family changed drastically. On April 7, 1933, the Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service was enacted, which cost many Jewish and other disfavored public servants their jobs. Despite this law, Wilhelm Masser was able to keep his position since he had fought on the front lines and had been appointed as a civil servant before 1914. In 1935, though, when the Nürnberger Gesetze (Nuremberg Laws) were passed, Jewish people were regarded as second-class citizens and all exceptions became invalid. Thus, Wilhelm Masser had to give up his position as a judge.

As a result of Kristallnacht of 1938, a night of rioting against Jews, he was deported to the Dachau Concentration Camp in an attempt to force him out of Germany and „Aryanize“ his assets. Masser was released only in January 1939. The cold winter, the forced labor and constant abuse took a toll on his health. He died in March 1940 and was buried by his family in Neuer Israelitischer Friedhof, a Jewish cemetery in Munich. His estate was confiscated and his wife Nelly, his brother Ludwig and Ludwig’s wife Gertrude were deported to Lithuania in the fall of 1941 and killed in Kaunas on November 25, 1941.

Only two children of the Masser brothers survived: Wilhelm’s daughter Elisabeth, who managed to flee to Great Britain in the first years of the war, and Ludwig’s son Wolfgang, who fled to Switzerland in 1939 when he was twelve years old, with the help of relatives.

9. Antonie, Elisabeth, Wilhelmine and Otto Mohr (stumbling stones at Hauptstraße 23)

Like most Jewish families that were living in Germersheim at the turn of the 20th century, the Mohrs had immigrated from the surrounding area. They were descended from Michel Mohr, a small business owner who lived in Oberlustadt in 1809. Michel’s grandson Maximilian, born in Germersheim in 1858, was a butcher’s son and cattle trader. At the time, Germersheim was a flourishing garrison town with a slaughterhouse and the demand for meat was increasing steadily, making it a profitable business location for Maximilian Mohr. He was therefore able to consolidate his business and set up house on Jakobstraße

183. His marriage with Klara Haas produced four children: three daughters by the names of Antonie (Toni) (1889-1942), Elisabeth (1890-1942) and Wilhelmine (1891-1942) and one son, Otto (1896-1942). All four of them remained unmarried and lived together in one household. The daughters farmed the land, while Otto, who was a cattle trader, business owner and temporarily also ran a cigar factory, took over his father’s company in 1923.

In November 1915, at the age of 19, Otto Mohr was drafted into the army, but he spent the war years far away from the fronts. As the successor of his father’s business, he purchased a property in central Germersheim in the mid-1920s. It was 1,680 square meters in size, located on Hauptstraße 127 (now 23), the busiest street of the town, and perfectly met the requirements of a cattle trader. The family lived in a two-story house that had several outbuildings as well as a laundry room and garages in the back. Two stalls for keeping livestock, a large barn with storage spaces for hay and straw, a shed as well as a large fruit and vegetable garden were also part of the property.

It was a time of economic hardship and Mohr’s property purchase aroused extreme envy among the citizens of the town. The National Socialists (Nazis) in Germersheim, who had been acting in a politically aggressive manner since 1927, stigmatized Otto Mohr as a figure of hate so that he consequently became a victim of racist stereotypes and prejudice. After the Nazis came to power in 1933, the local Nazi group organized a degrading spectacle which went down in history as the „Germersheim walk of disgrace“: On June 22, 1933, Otto Mohr and the well-known politician August Ebinger were arrested and dragged onto Königsplatz by some members of the Sturmabteilung, the paramilitary wing of the NSDAP (National Socialist German Workers’ Party). There, signs were hung around their necks, and they were presented to a jeering crowd. While Ebinger’s sign read „I’m to blame for the town’s ruin“, the inscription on Mohr’s sign stirred up the infamous prejudices against self-employed Jews: „I have exploited the German people for years“. They then had to walk through the town, with people standing on the sides and taking their hatred out on the two men.

Retrospectively, it is hard to understand why the Mohr siblings remained in the country after that. At the end of December 1937, Otto Mohr was permanently banned from working in his profession. While the sisters decided to hold on to their farming land, Otto somehow made his way to Belgium in 1938 and found accommodation in Saint-Gilles near Brussels. Having escaped Kristallnacht of 1938, a night of rioting against Jews, he was identified as an „enemy alien“ and deported to the Saint-Cyprien Internment Camp near Perpignan in southern France after the attack of the Wehrmacht (German Imperial Forces) on the Benelux countries. Later, he was probably moved to the internment camp in Gurs, France. In October 1940, his sisters were also deported from Germersheim to Gurs. After 22 months in the camp, the women were moved to the Drancy Transit Camp near Paris in August 1942. On August 10, 1942, they were deported to the Auschwitz Concentration and Extermination Camp (in present-day Poland) in the so- called „Transport No. 17“. Only a few hours after their arrival, they were murdered in the gas chamber.

Otto Mohr had attempted to escape and go into hiding in Vichy France, which was still unoccupied at the time, but he was arrested and handed over to the Oranienburg Concentration Camp near Berlin. On September 24, 1942, he was also deported to Auschwitz. After that, the Germersheim branch of the Mohr family ceased to exist. Antonie, Elisabeth, Wilhelmine and Otto Mohr were formally declared dead by the Germersheim Municipal Court on May 6, 1949.

Even after the war had ended, hardly anyone showed interest in the fate of the Mohr siblings, for apparent reasons: Quite a few citizens of Germersheim had benefitted from the deportation. They repressed their former attitudes and behavior they had once expressed so openly by simply not discussing what happened in the past or playing it down. By 1942, local government officials had already reduced the value of the Mohrs‘ house. In the 1950s, the family’s vast farmland was also sold to local farmers and constructors – at very low prices.

10. Alfred Isaak Plaut (lived in Germersheim 1914-30, no stumbling stone)

Alfred Isaak Plaut was born in Krefeld in the Rhineland in 1884 as the son of a store owner. As a child, he moved to Fußgönheim, a small town near Ludwigshafen am Rhein, the hometown of his mother Fanny Herz. He was the second of three children of a Jewish family (he had an older sister named Rosalia and a younger brother named Edmund) and after secondary school, he took up his father’s profession. Since he was fluent in French, he repeatedly stayed in Paris for extended periods of time. Shortly before the beginning of the First World War, he left Paris to evade the impending internment as an enemy alien. Thereafter, he opened a clothing store in Germersheim, but could not keep it for long because of the army’s mobilization. Plaut was assigned to the military hospital at the Germersheim fort as a sergeant and was eventually promoted to technical sergeant. Soon, however – as an alleged Francophile and Jewish soldier – he was suspected of being a spy. Since no evidence could be found, he was relocated to the Western Front in November 1917. He was awarded the Iron Cross 2nd Class, but was badly wounded during the German spring offensive in 1918 and spent the rest of the war in a military hospital.

After the end of the war, Plaut returned to Germersheim and dealt in raw materials for the local enamel factories. In 1923/24, he and his associate, the master painter Karl Buttweiler, were among the half a dozen local enamelware producers. At the same time, Plaut entered the arena of local politics. In 1924, he was elected to the City Council as one of four city councilmen from the SPD, the Social Democratic Party of Germany. By December 1926, however, he resigned from office. The reason for the sudden resignation from his mandate is unknown.

In the subsequent period, Plaut divested his share of the company and moved to Geispolsheim near Strasbourg in 1930. At the end of the year, his elderly mother passed away in Fußgönheim. He did not maintain ties with Germersheim, where he had lived for almost 16 years. One exception was his correspondence with his former employee Emil Müller, who by then was a manager at another enamel factory. Müller lost his job in February 1933 and emigrated to Alsace in May 1933 to escape the National Socialists (Nazis). Plaut helped his political companion to put down roots.

Plaut’s marriage to the Frenchwoman Martha Emilienne Dorin and his entrepreneurial activities consolidated his status in France until the Wehrmacht (German Imperial Forces) occupied Alsace in June 1940. At the beginning of 1941, his German citizenship was formally revoked. Unlike his younger brother Edmund, who died in the Le Vernet Internment Camp in France in 1942, Alfred Plaut survived the time of occupation and persecution between 1940 and 1945, but he was in frail health. In March 1946, he passed away during a stay at the health resort in Luxeuil-les-Bains (Belfort) at the age of 61. He and his wife remained childless.

11. Noë, Arthur and Friedrich Rosenbaum; Louis „Lui“,

Elsa, Günther und Ingeborg Rosenthal

(stumbling stones at Hauptstraße 9)

In 1891, when Noë Rosenbaum was 27 years old he moved from Franconia to the small Jewish community in Germersheim to be with his wife Fanny Vollmer. Her father Samuel Vollmer had owned a fabric and clothes shop on Hauptstraße 135 since 1860. In 1899, Noë bought a house where he could both live and run a business that mostly sold female clothing. His wife, who was a trained milliner, contributed to the success of the shop. The building which housed the couple, their children and later their grandchildren was near the shop of Samuel Vollmer on Hauptstraße 134 (now 6). In the early 20th century, Noë and two partners also ran the cigar factory Lorenz in Lingenfeld near Germersheim. At the same time, he was elected head of the local Jewish religious community. He held this office from the end of the First World War until the community was disbanded.

Noë and Fanny Rosenbaum had three children: Elsa (born in 1893), Friedrich Salomon (born in 1894) and Arthur (born in 1900). Friedrich volunteered to fight in the First World War on the Western Front when he was 19. He was praised for his impeccable conduct, but after demobilization he returned penniless to Frankfurt, where he had previously trained in commerce. In 1921, he married Mathilde Wachenheimer, the daughter of a Jewish merchant. She passed away in 1931, when she was just 37 years old. Friedrich Rosenbaum was forced to move to one of the Jewish ghetto houses in Frankfurt in 1939/40 and was deported to Kaunas in Lithuania in November 1941. Shortly after his transport arrived, they were taken to the infamous Fort IX, where Friedrich and the other deportees were shot dead. He was one of 100,000 victims buried in mass graves.

In 1919, Elsa Rosenbaum married the merchant Lui Rosenthal. He was the partner and designated successor of Elsa’s father until he passed away at a young age in the mid-1930s. After the First World War and during the French occupation, the living conditions in Germersheim worsened and the Rosenbaum/Rosenthal family experienced severe economic hardship. In 1951, the Volksbank in Germersheim still had record of a debt of 200 German Marks from a loan. After her husband’s death, Elsa Rosenthal had to take care of her school aged children and her elderly father, all during the harsh conditions of the Nazi regime.

The youngest son Arthur Rosenbaum trained in commerce in Mannheim, where he also lived with only a short interruption. In 1929, he married Ida Postel, a protestant from Ludwigshafen. This „mixed-race“ marriage would not hold up for long under the growing social-political pressure. In 1935, the Nürnberger Gesetze (Nuremberg Laws) came into effect, which classified German Jews as second-class citizens and the Gesetz zum Schutz des deutschen Blutes und der deutschen Ehre (law concerning the protection of German blood and honor) took away their basic human rights. The Christian-Jewish couple didn’t divorce but they lived separately: Ida in Ludwigshafen and Arthur in Mannheim. Arthur was likely trying to protect his wife, who was „jüdisch versippt“ (meaning she had family ties with Jews), from any reprisals. In 1940, he was deported to the Gurs Internment Camp in southern France. To escape the harsh conditions in the camp, he opted for work for the G.T.E. (Groupement de travailleurs étrangers: Foreign Workers Group). Here he carried out forced labor near Toulouse. In 1942, he was deported from the Drancy Camp near Paris to the concentration and extermination camp in Auschwitz (in present-day Poland). There his trail is lost and in 1952 the municipal court in Mannheim declared him dead pronouncing New Year’s Eve 1942 as the recorded date of death.

In early 1938, the business that had been most recently run by the widow Elsa Rosenthal was on the verge of bankruptcy. The boycott of Jewish businesses, the numerous restrictions, as well as the death of her father forced Elsa to move with her children Günther and Ingeborg Rosenthal to Frankfurt am Main. During Kristallnacht (1938), a night of rioting against Jews, the eighteen-year-old Günther was arrested and brought to the Dachau Concentration Camp. He was released after being held for three months. The young man planned to escape to Palestine, but he only got as far as Yugoslavia, where he was captured by German troops. He was probably among the Jewish refugees of a steamship transport to Palestine, detained on the Danube. In October 1941, Günther Rosenthal, along with 2,100 other men, was taken to Zasavica in Yugoslavia, later the location of the Sremska Mitrovica Concentration Camp (in present-day Serbia). He was shot as part of a retaliation for partisan attacks. Soon after, his mother and his sister Ingeborg were deported to the Łódź Ghetto (in present-day Poland). There, their trail is lost, and they were declared dead after the war.

The Rosenbaum estate, which was confiscated in 1941, was to be returned to the family after the war. However, due to expenses incurred by the Finance Ministry of Rhineland Palatinate when securing the property after a bombing, the „Rosenbaum Jew house“ (as it was still referred to by the revenue office in Germersheim in 1949) was torn down by the local construction company Ludwig Roth and the plot sold to Eugen Nebel from Germersheim. There is nothing left of the Rosenbaum and Rosenthal families from Germersheim.

12. The Schriesheimer Family (lived in Germersheim, Hauptstraße until the 1930s,

no stumbling stones)

Moritz Schriesheimer, the son of a cattle trader from Leutershausen an der Bergstraße, left his hometown after the passing of his parents in 1898. Shortly afterward, he married Bertha (Betty), who was four years his senior. Bertha’s father was the late Rülzheim tailor and shop owner, Isaak Feibelmann. In 1900, the 26-year-old merchant Moritz opened a store in Germersheim (Hauptstraße 126) which offered a variety of goods, ranging from clothing to toys and tobacco products. He also produced mineral water under the label „Zur billigen Quelle“ (The Generous Spring), which he distributed to the on-duty soldiers in the town, as their approved source of drinking water. In 1907, the Germersheim address directory listed Bertha by her maiden name even before her husband, who was the actual owner of the store. The order of the listing was unusual for the time and indicates that they were likely equal partners in marriage and that Bertha had brought a dowry which probably facilitated the establishment of the store. Both followed the cultural and religious rules of the rural Jewish population common in the south of Rhineland-Palatinate, especially adhering to the dietary restrictions. The couple had five children born in their Germersheim home which consisted of their living space and the family-owned store. The children’s names were Anna Elisabeth (Liesel, 1901), Hilde (1902-1903), who died as an infant, Erna (1906), Gertrude (1908) and Friedrich (Fritz, 1911).

The First World War had a major impact on the middle-class family’s financial situation as the shortage of goods and increasingly strict rationing was a blow to the store’s revenue. In May 1915, Schriesheimer was called up to serve in the 2nd Company of the Germersheim army reserve as a guard in the prisoner- of-war camp located outside of Germersheim. He stayed in this position until demobilization in 1918 and was commended for his good leadership. After the ceasefire had been agreed, the city lost its garrison and with it almost half of its population. Due to inflation and increasing poverty, the purchasing power of the inhabitants fell drastically which also had a major impact on the Schriesheimer business.

It was not until the eldest daughter, Anna Elisabeth, married that the family’s financial situation improved. In 1925, Anna Elisabeth married Henri Charles Mialhe, a French soldier serving in Germersheim and a qualified bookkeeper and moved to his home in Mazamet in the South of France. Four years later, her sister Gertrude, who had just come of age, followed in her sister’s steps and married Leopold Farkas in December 1937, a native of Hungary, with whom she ran a lingerie shop in Paris. In 1926, Schriesheimer’s daughter Erna, 20 years old at the time, started to work as a typist before she later became a secretary for the Bund Israelitischer Wohlfahrtsvereinigungen Baden e.V. (a Jewish charity organization) in Karlsruhe. It was also in 1926 that the 14-year-old son Fritz began an apprenticeship at the local bank, Stadtbank Germersheim, where he worked until the end of 1930.

Since the 1920s, Moritz Schriesheimer represented the Jewish religious community in Germersheim as the second board member. This activity, his French son-in-law and his „pro-French attitude“ were the reasons why he was spied on by the Germersheim police, which reported to the Munich police directorate that was responsible for political affairs and counterintelligence. To escape the increasingly anti-Semitic repressions, the Schriesheimers, labeled as „untrustworthy“ by the Nazi regime, sought refuge in the protective anonymity of Karlsruhe. As a result of the involuntary liquidation of his business, Moritz Schriesheimer no longer had any income and was dependent on the support of his children. Embittered, the 64-year-old merchant finally died on October 6, 1937. The arbitrary behavior of the authorities continued to complicate the lives of his children. For example, when Erna and Fritz Schriesheimer applied for a passport at the passport section of the Karlsruhe police headquarters in November 1937 in order to travel to Paris to attend their sister Gertrude’s wedding, the application was rejected without comment at the instigation of the Gestapo, or secret police force, at the police headquarters in Karlsruhe.

After the passing of her father, Erna Schriesheimer looked after her mother Betty Schriesheimer. As of spring 1938, the 32-year-old headed the Karlsruhe office of the Israelitischer Wohlfahrtsbund. In 1939, the two women prepared for their emigration to the United States to escape the anti-Semitic atmosphere. They wanted to wait in France until the visa was granted. However, while the police in Karlsruhe was still processing the passports (that were only valid for twelve months anyway) and verifying that they did not owe the state any taxes, the war started and the escape route to the neighboring country was blocked.

On October 22, 1940, the Gauleiter (heads of the administrative districts) of Baden, Robert Wagner, and Saar-Palatinate, headed by Josef Bürckel, deported the remaining 6,500 Jews in their districts. They were forced into trains that took them to an internment camp in Gurs, France, at the foot of the Pyrenees. Erna and Betty Schriesheimer had to abandon their apartment within two hours and had to leave everything behind – save for 50 kilos of hand luggage and 100 Reichsmarks. The Gurs Internment Camp was overcrowded. In combination with disastrous sanitary conditions, cold, hunger and lack of medical care, this led to a high mortality rate among camp prisoners. In February 1941, the camp administration released Betty and Erna Schriesheimer because of health issues and possibly also because Fritz had, in the meantime, voluntarily joined the French army. Betty Schriesheimer was allowed to move in with Elisabeth, her eldest daughter, in Brassac-les-Mines on the condition that she would immediately report to the local authorities and gendarmerie. Eventually, Betty had to go into hiding, but survived the war thanks to her family in France. In April 1945, however, affected by the stress and hardship she experienced as a result of expulsion and persecution, she passed away.

Outside the camp, Erna was able to travel freely within France so that she could make progress on her emigration application in a race against time. In May 1941, she appealed to the US consulate in Marseille and managed to obtain an alien’s passport in Clermont-Ferrand. The visa required a sponsor and since an unknown US-American had acted as such for Erna Schriesheimer, her US-visa arrived six months later. In Marseille, Erna boarded a ship that took her across the Mediterranean Sea, a war zone at the time, to the Western Algerian port city of Oran. She then continued by train to Casablanca and came to New York via steamship. When she arrived in New York in March 1942, she was just as penniless as many other refugees and led a humble life as maid between 1942 and 1952. Not until late 1944 could she finally get in touch with her family in France again.

Through her marriage to Otto Löwenthal, a merchant who had fled from Frankfurt, she finally gained financial security. In 1953, the couple moved to Milwaukee, Wisconsin. From that point on, Erna Schriesheimer-Löwenthal constantly fought the German government for compensation. In contrast to her two sisters, who had moved to France before 1930, she was indeed able to prove the damage to property and assets with the respective documents and therefore assumed a leading role throughout the legal proceedings. At the District Court of Karlsruhe, she filed a complaint for compensation of home furnishings that had been confiscated from her parents and initially attempted to recover 19,529 German Marks. The opposing side, however, argued that the auction proceeds of the household items in 1940/41 had only amounted to 2,190.60 Reichsmarks. There was no mention that former Jewish property was regularly sold at prices far below market value. This measure was instituted to ensure loyalty to the Nazi regime by regular citizens, who would profit from those measures. In 1960, Erna Löwenthal-Schriesheim and her three siblings reached a settlement with the opposing party which gave them 50% of their claim, a modest sum that had to be shared among all four siblings. Additionally, Erna herself was compensated for her so-called „imprisonment“ – the deportation and 115 days in the internment camp – with as little as 450 German Marks. The final settlement in 1966 marked the end of her struggle for justice that had gone on for more than two decades. Shortly after in 1968, Otto passed away, followed by Erna only a few months later.

Fritz Schriesheimer had worked as a bookkeeper with Blicker, a textile company in Karlsruhe, until he was dismissed in 1935 due to the „Aryanization“ regulations. Lacking any job prospects, in September 1938, he decided not to wait out the lengthy visa approval process and fled to France. As he did not have a work permit, he could not work in France. When the war started, Fritz Schriesheimer was interned but opted to serve in the French army instead. He fought with the French foreign legion in North Africa until he was discharged in September 1940.

In his life story written for the State Office of Restitution in Baden-Wurttemberg, he recounts how he was taken to a forced labor camp in Béchar, formerly known as Colomb-Béchar, Algeria, soon after he was discharged from military service. With little nourishment and in the stifling Saharan heat, the workers were forced to break up large boulders that were used to lay railroad tracks. In February 1941, he was finally freed from a second camp in the Algerian town of Kerzaz. Once back in France, he first worked as an agricultural laborer and later hid among farmers using false papers until the liberation of France from the Nazis. In 1948 he married a Jewish woman with two children, whose first husband had been deported and killed in one of the camps.

In the proceedings against the compensation authority of the state of Baden-Wurttemberg, Frédéric Richemer, an alias that Schriesheimer took on after the war, attempted to claim compensation of 21,578.40 German Marks, citing damage to his professional advancement. When he was offered only 8,315 German Marks in 1957, deeply disappointed, he outright refused to accept the offer. Instead, in 1964, he again filed for a complaint for personal injury, citing a neuro-psychiatric expert opinion issued in Paris, in which he was diagnosed with depression, suffering from persecutory delusions, and partial incapacity to work due to the persecution he had experienced. Schriesheimer’s claim was rejected by the 2nd Chamber of Compensation of the Karlsruhe District Court in 1970 and by the Karlsruhe Circuit Court of Appeals in 1972. The rationale for the decisions was that the independent French medical examiners had failed to bring forth any exact medical evidence for their findings. The court’s decision was based on the testimony of Karl Peter Kisker, a professor at the University of Hanover, who would regularly diagnose psychological disorders of Holocaust survivors as merely „temporary states of exhaustion“. Kisker’s diagnoses essentially aided and abetted the systematic oppression of Holocaust survivors. After eight years of litigation, Schriesheimer was forced to settle for a meager compensatory amount. In 2003, the Germersheim native passed away in a remote village in the Brittany region of France.

13. The Schwall Family (lived in Sondernheim in the 1920s,

no stumbling stones)

Arthur Schwall and Eva Heitner were self-employed actors who had married in Berlin in 1922 and had a son, Hans Helmuth, who was born in Sondernheim in 1923. After marrying, they had moved to Arthur’s hometown of Daxlanden, a borough of Karlsruhe where his family owned a restaurant. Arthur’s artistic career remained only moderately successful, compelling him to take up a side job as a supervisor at a brickyard in Sondernheim, around the time his son was born. From 1929, he started working full- time as manager of the „Kronen-Lichtspiele“ movie theater in Daxlanden. His non-orthodox Jewish wife, daughter of a costume tailor, was born and raised in Berlin where her stage career took off in various theaters in 1915, according to a compensation claim filed in 1957. In 1917, she received a long-term contract deal with the Grand Ducal Court Theatre (today known as the Oldenburg State Theatre) in Oldenburg. She later went on to perform with a traveling theater (Hessische Landeswanderbühne) in Darmstadt. After their marriage in 1922, Arthur and Eva both performed in the united city theater of Aarau and Chur in Switzerland. In 1926, they started performing at the Baden Stage (Badische Bühne) in Karlsruhe until the National Socialist (Nazi) regime brought Eva Schwall’s stage career to an abrupt end.

Under Nazi rule, race-based exclusion from the Reich Chamber of Culture and the Reich Theater ended the career of the 36-year-old actress. Her so-called „privileged mixed marriage“ to a Christian was not enough to shield her from discrimination. Eva Schwall sold tickets at her husband’s movie theater until 1936, when she was prohibited from doing so by the local Nazi Party leader. Over the years, she continued to be harassed by the Gestapo, the secret police. On multiple occasions, she was summoned to appear in court for reasons including picking flowers in „German“ forests and not wearing the Jewish star, which she, as the wife of an „Aryan“, was not legally required to wear. She was also targeted for sending a package to a Jewish woman from Germersheim, Bertel Kahn, who had been sent to the Gurs internment camp in France.

In early February 1945, she was to be deported to the Theresienstadt Ghetto (in present-day Cech Republic) along with all the other Jews living in mixed marriages who still resided in Karlsruhe. In a desperate attempt to save his wife, Arthur Schwall turned to his friend and practicing gynecologist, Dr. Philipp Schmid, who was well-known for his anti-Nazi views. Schmid administered an injection that resulted in Eva Schwall coming down with a high fever. Subsequently, she was declared unfit for transport by the public health officer. However, the couple continued to live in constant fear.

On April 4, 1945, Karlsruhe was occupied by the French military. Eva Schwall was now safe, her mental health, however, was permanently impaired because of the ban from her occupation and the fear of deportation. For the rest of her life, she suffered from heart trouble, paralyzing fear of death and persecutory delusions. Her application for restitution that was submitted in August 1949 was rejected in February 1953. The decision was based on the expert opinion report issued by the Rudolf-Krehl-Klinik in Heidelberg. According to the report, her psychological impairment was based on menopausal symptoms and her persecution was merely a „contributing factor“. As a result, the court found only a 30% reduction of earning capacity. When Eva Schwall’s lawyer appealed the decision in 1957, a settlement was quickly reached, whereby she would receive a monthly pension payment of 147 German Marks. After a nerve-racking fight for justice, the 62-year-old Eva Schwall accepted a compensation payment of 7,500 Reichsmarks.

Hans Helmuth Schwall was born on September 27, 1923 in Sondernheim, which has been part of Germersheim since 1972. As child to a Jewish mother, Hans Helmuth Schwall was categorized as a „half- Jew of the first degree“ according to the Nuremberg Laws. Against his own will, he had to join the Hitlerjugend (Hitler Youth), only to be excluded shortly thereafter due to his non-Aryan mother. Since December 1936 every child from the age of 10 had to join this organization. In the meantime, all other youth organizations and clubs were prohibited. Even in his uncle’s restaurant, the family was no longer welcome. At the age of 18, Hans Helmuth Schwall witnessed an interrogation of his mother by the Gestapo.

Hans Helmuth Schwall attended a commercial school and planned to transfer to a commercial college. He did not pass the required entrance exam, though, and later assumed this was based on his descent, as „half-Jews“ were no longer encouraged to attend secondary schools. He completed an apprenticeship at and later worked for the newspaper Badische Zeitung in Karlsruhe. In 1941, he was given a military medical examination, in which he was deemed as „unfit for service“. Therefore, he could not be recruited and continued working for the newspaper that was also printing ration cards for Karlsruhe. In March 1944, around 2,000 individuals were rounded up for forced labor. This group consisted of „mixed“ Jews, men married to Jewish women, and Roma who were transported from the Karlsruhe train station to Saarlouis. Among those transported to Saarlouis was Hans Helmuth Schwall. It was made unequivocally clear to his parents that they would be deported to a concentration camp if their son ever escaped.

Until September 1944, the deportees had to work in 12-hour-shifts, night and day, alongside prisoners who had been released from jail. They were forced to build underground storerooms and production facilities along the banks of the Seine River. In August 1944, Hans Helmuth Schwall was commandeered to work as a trucker for a transport unit near Rouen, France, to expedite the mass retreat to Germany as the Allies were advancing. Ultimately, Schwall and his fellow forced laborers received orders to go to Essen. From Essen, he was able to return to Karlsruhe. The family survived the war and the oppression of the Nazi regime, but they paid a high price for it.

14. Auguste (Gustel) Margareta Victoria Töpfer

(stumbling stone at 17-er Straße 13)

In the early 1990s, a street was named after Auguste (Gustel) Töpfer, one of the most widely known Jewish Nazi victims in Germersheim. An inconspicuous, dead-end road on the outskirts of Germersheim was named Gustel-Töpfer-Straße in memory of „all“ victims, according to an official statement.

The backstory and discussions leading up to the official commemoration reveal a lot about local politics at the time. In May 1985, on the 40th anniversary of the collapse of the Nazi regime, marking the end of the Second World War, the SPD (Social Democratic Party) faction of the city council requested that the street where the Töpfers once lived in the city center (Schiller Straße, today 17-er Straße) be dedicated to them. Additionally, a memorial plaque was to be placed at the site of the former synagogue on Oberamtsstraße. Although most of the council was in favor of naming a street after Töpfer, no concrete action was taken for a long time, as they could not agree upon which street to dedicate in her name. The following year, the Green Party advocated for the newly revamped neighborhood square, where Eugen- Sauer-Straße and Sandstraße intersect, to be named after Gustel Töpfer and to be designated as a „Kommunikationsplatz“, or a place for residents to gather. However, years after the idea initially came to mind, Töpfer, murdered in Auschwitz in 1942, had a street dedicated in her name whose location is obscure and unlikely to attract any attention.

Auguste’s father, Bernhard Töpfer, had immigrated to Germersheim from Bohemia and in 1888 founded a wholesale graphite, talcum and pigment company in a building that today is located at No. 13, 17er Straße. The wholesale firm was operated together with a shoe and oven polish shop in the rear building located at the same address. Shortly before opening the business, the 29-year-old Bernhard had married Emma, the eldest of local factory owner Josef Dreyfus’s eight children. Dreyfus operated a factory that produced matches and polish in neighboring Lingenfeld simply called the „Chemische Fabrik“, or „chemical factory“. Bernhard’s daughters Friederike and Auguste were both born in their maternal grandparents’ house in Lingenfeld. Bernhard had enjoyed a comfortable middle-class life until his unexpected death in 1911. Six years later, his wife also passed away. Friederike had long since died in 1902 at the young age of 14, so that by the late fall of 1917, the 22-year-old Gustel Töpfer found herself alone in the world.

According to a town register from 1906, the family of four all belonged to the Jewish faith. After Bernhard Töpfer’s passing, however, his widow and remaining daughter turned to the Catholic faith until they legally converted in 1917 or 1918. They were not the first Jews in Germersheim to convert to the Christian faith. In 1915, Rudolf Kahn had also converted from Judaism and had become a Protestant. Auguste, however, was not baptized until March 1918, about four months after her mother had passed away. It can only be assumed that Emma played a crucial role in her daughter’s conversion, as her death record from the civil registry office indicates that she was a Catholic at the time of death. However, religious conversion did not shield anyone from the racial-ethnic ideology and ideas with which the Nazis denigrated and disparaged Jewish people. Unfortunately, Auguste Töpfer would come to experience this firsthand. Since 1933, the practicing Catholic was subjected to the same restrictions and systematic harassment as the „Glaubensjuden“ or practicing Jews.

In the fall of 1938, Auguste Töpfer’s property was caught in the crosshairs of local avarice and greed. Her apartment was subsequently confiscated, an action justified by Nazi racial ideology, although she was permitted to remain in her own home, albeit temporarily. In the early morning of October 22, 1940, Töpfer along with the Kahn family and the three Mohr sisters, taking with them only a few personal belongings, were taken by bus to Landau, and from there loaded onto trains with other Jews from the Saar Palatinate and Baden regions, and subsequently transported to the Gurs internment camp at the foot of the Pyrenees in southern France. There, Gustel Töpfer lived a life of deprivation. Meanwhile in Germersheim, the Reich, the district (Gau) and the local Nazi group confiscated her remaining possessions and property.

Near the end of August in 1942, she was deported to the Drancy internment and transit camp on the outskirts of Paris. On September 4, 1942, Transport No. 28 rolled eastward in the direction of Auschwitz. Töpfer’s trail is lost soon after she arrives and is put through the selection process. On February 14, 1949, the Germersheim Municipal Court declared Gustel Töpfer dead. Her actual date of death is recorded as being on December 31, 1942.

15. Flora Weil (born in Germersheim, no stumbling stone)

The biography of Flora Weil, born on October 4, 1884 in Germersheim, cannot be reconstructed completely. The repeated displacement of Flora Weil and her family, however, reflects the restrictions and humiliation Jewish people endured at that time. In the 1880s, her father, Albert Scharff, ran a small cigar-manufacturing shop in Germersheim. Afterwards, he ran a shop that sold tobacco and shoes in Landau (Palatinate region), where both Albert Scharff and his wife Marie were from. Flora Scharff became the wife of Theodor Weil, born on August 13, 1872, a shop owner whom she followed to Strasbourg in 1905. On June 28, 1906, their only daughter, Gertrud, was born in Strasbourg. From 1905, Theodor Weil ran the family-owned brandy and liqueur distillery, S. Weil & Cie, along with Seligmann Weil, who was aging and in poor health. From around 1912 to 1913, he ran the company on his own.